Over the past week I’ve been formulating write-ups on META 0.00%↑ CDLX 0.00%↑ and CVNA 0.00%↑. During said process, I realized that it may be beneficial to first share how I think about investing in a general sense. The ownership overlap between CDLX and CVNA is quite high (check 13F’s, it’s honestly surprising). I’d imagine a large portion of this is related to Cliff Sosin of CAS championing said investments, however the underlying thematic is strikingly similar despite the exceptionally different businesses.

While selling used car loans and bank app advertisements could not be less similar business and financial models, both companies (and META) fall into a bucket of exceptionally high uncertainty. There is no guarantee CVNA will be solvent in a year. There is no guarantee it won’t be a $15b market cap in one year. There is no guarantee JPM won’t leave CDLX. There is no guarantee CDLX won’t 10x over the next 3 years.

While many will tell you they enjoy volatility (good lord is this in so many letters) they largely mean volatility in price, not volatility in businesses outcomes. The popular adage is “I will gladly buy a dollar for a dime.” This is of course exceptionally obvious, not indicative of any sort of enlightenment. If you did NOT do that as a fund manager you should likely close your fund. Business volatility is a harder pill to swallow.

Nobody wants to be guy explaining to LP’s how he blew up 30% of the fund on Carvana. After all, the news said it was bad, so why were you invested? Car prices were turning over wasn’t it obvious? They were highly levered and rates were rising are you an idiot? If BRK.B dropped 90% overnight investors would berate managers for not buying more. CVNA I’d bet does not have a similar luxury.

Where CVNA and CDLX differ from the common wisdom, is they have exceptionally high intrinsic value volatility as opposed to simply share price volatility. By this I mean that the underlying variability of business outcomes will be much higher that your average company. I find these to be exceptionally attractive, not painful.

In reality your returns will look no different if you are up or down from share price volatility or intrinsic value volatility. I could not care less where my volatility comes from. I could not care less if Twitter thinks I’m an idiot (in fact please explain to me why!) I care only about the future implied returns from the current situation.

What creates said returns is the probability skew of outcomes. Many would call this conclusion exceptionally obvious and I would agree! Where I would disagree is in the ease of evaluating these situations in each different type of volatility.

The following Twitter “trick math question” came across my feed recently and does an excellent job of explaining my point.

If you’re feeling particularly smart, you can laugh to yourself and choose the green button. You can write a comment about how 50% of $50m is an EV of $25m, much higher than the guaranteed $1m. Congrats, you solved price volatility by not selling your 50% $50m for $1m.

Now let’s extend the problem - After you press one of these buttons, you are given an opportunity to pay $1m for a 50% chance at $101m ($150m total) and 50% to simply lose your $1m ($49m total). You are of course a genius, you will solve price volatility and maximize EV. You choose the 50% chance both times, you increase your expected value from $25m on the first press to $49.75m on the second press. You are a genius, whether you win or not. Pat on the back.

Now let’s assume you press the red button and are offered the same follow up scenario. Given a $1m cost to press the button, it can simply be reframed as a 50% chance at $100m. The EV ends up being $50m, marginally higher than the math wiz maximizing instant EV. Funny how that works. The intuitive answer ends up being incorrect and you make less money. Funnily enough the correct answer also depends on price. What is intuitive may still be correct if the numbers make sense!

Unlike button presses, businesses and investors often don’t have the benefit of explicit probabilities and outcomes. Companies such as CDLX, CVNA, and META will need to make a chain of bets such as investing for growth in Q1 for CVNA, META investing in VR, and CDLX investing in a new ad server. Us investors will then need to make our own bets on how well these companies can make probabilistic bets, with limited idea regarding what future bets will be made.

In the above example, what if the green button is a lie? Do they even have $50m? Are the button mechanics audited or is it rigged? If it is audited can we trust the auditors? Clearly whoever is letting me press this button is running a structurally unprofitable business and likely has some kind of related party transactions going on to inflate their personal wealth.

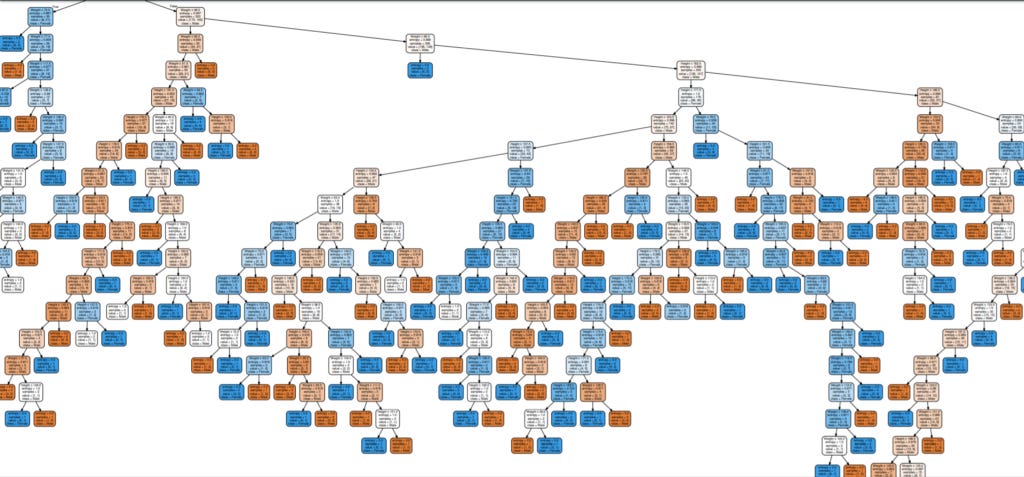

The overarching idea is simple, our decisions aren’t based on simple button presses. Reality is much more complex and it looks more similar to the below:

This image is a sample of a ML decision tree, let’s assume each “branch” has a probability of a business decision and each “leaf” a corresponding valuation. This would be an effectively unsolvable problem, even the most sadistic (and stupid) of PM’s isn’t going to ask you to model hundreds of scenarios. While the human thought process is similar to that of a ML model, unfortunately we lack similar processing power, yet still are assigned with valuing said situations regardless.

We as investors MUST assign probabilities to events, numerous at a time in fact, value the outcomes of all of these probabilities, and determine how that outcome compares to thousands of other outcomes on the market. I’ll skip the review of Kahneman’s work (and avoid recommending books that are 200 pages too long) to simply say that this is exceptionally difficult to do accurately.

Given our limited time in this mortal coil and even further limited time to read about companies, we must make judgements about what is important and what is not. To do so we utilize our neurons ability to recognize patterns, take judgement calls on what is important, and rapidly assign probabilities to future events based on our previous understanding of the world. To once again skip review of a far too long book (Tetlock’s Superforecasting), it turns out that regardless of how much of an “expert” you are, most people are terrible at this.

So what is my point? Share price volatility is actually pretty easy to deal with, you don’t need to update your existing models, you don’t need to grapple with numerous new developments and rewrite a full mental picture. You can happily buy more when your model says to. Intrinsic value volatility on the other hand is much harder to deal with. You must now grapple with your own mind, update an exceptionally complex decision tree with incremental information, and understand what future bets may look like. You must determine what is important to review and then do so. This has been objectively proven to be quite difficult and obviously time consuming, yet intuitively will create exceptional opportunity for those with the ability to consistently navigate.

Now perhaps it is hubris, but I believe my capabilities to navigate intrinsic value volatility is materially differentiated from the average market participant. Many of you readers will believe this as well, regardless of your faux humility, otherwise you’d simply buy the index. (Obviously the majority of us will be wrong, and therein lies the rub.) Regardless, under the assumption I have some idea of what I’m talking about, my investing philosophy is rather simple. I wish to buy into companies with high intrinsic value volatility where my view of end state is materially differentiated from what is implied by the current price.

The hypothesis then for CVNA and CDLX becomes quite clear. I believe that these companies have a high number of highly uncertain key drivers, which leads to a material mispricing of their share price if I can create a differentiated view on how said drivers will impact the intrinsic value of the business. CDLX for example is rolling out a new ad server that has minimal coverage of capabilities, has seen significant C-Suite turnover, has no indication of stable OpEx spend, and saw their largest and only direct competitor acquired by their largest customer. CVNA is in the midst of a used car recession, with falling prices looming on the horizon, after heavily overinvesting and leveraging their balance sheet into a poor macro environment, reliant on uncertain ABS markets, and stable state OpEx/GPU are obfuscated by Covid growth and other factors. I believe the upside to these scenarios is far more likely and reward weighted than the downside implies.

If my ability to critically review complex scenarios is indeed differentiated, then these types of situations represent a fertile pool to fish in compared to the likes of your TDG’s/MCO’s/SPGI’s. At the highest level, I believe this to be a primary reason behind the significant shareholder overlap between the two companies, especially for those still invested after a rocky YTD performance.

So why do I have confidence in my “alpha”? First let’s understand the market we operate in. If we wind it back 50 years. the stock market was an entirely different beast. Information asymmetry for nearly any company was easily achievable. Today we live in a digital age where access to company financials, SEC filings, expert calls, alternative data, etc, is all to some extent table stakes. While some bears on Twitter are a fan of reading these wrong, I do not bank on my market opposition being ignorant. I do however believe it is significantly likely that misunderstanding will occur in situations such as CVNA and CDLX where the number of high importance and low clarity drivers is high. Taking cognitive short cuts that would be of minimal difference in your near index tracking positions can be of drastically higher impact in these companies, and far easier to fall into. Reading the exact same information we can come to drastically different conclusions, and I believe CVNA and CDLX are some of the greatest examples of such.

Our current era of loss making juggernauts is quite new. Many of the “old guard” has been trained to filter out these companies for decades. They have then gone on to spread these lessons to their students. Furthermore, the $AMZN’s of the world are quite unique. Many analogues have quickly gone bankrupt despite high flying promises. If you take a look through vocal $CVNAQ accounts, many have been in the game for quite awhile with a background in commodity stocks/credit markets, hardly known for their outside capital funded perpetually loss making companies actually sustaining operations. Purely from a base rate perspective, investing in CVNA and CDLX is likely idiotic, so writing them off with minimal mental load is thus the norm.

That said, information and forming a proper base does not a good investment make. While generally not a fan of quotes, I find the below quite apt.

I frankly believe that many investors do not fully appreciate this idea. Your “deep research” “industry contacts” and “proprietary models” do not equate to understanding what is actually important. GameStop for example was by all means a terrible company on the verge of bankruptcy. Yet funnily enough despite nailing the numbers, funds were forced to close or saw significant losses as they missed the meme forest for the trees (and fucked up risk controls but I digress) I have heard this concept described as a “wisdom asymmetry” as opposed to an “information asymmetry.” Understanding both where you’re at and what that means is the key, which brings us to our conclusion.

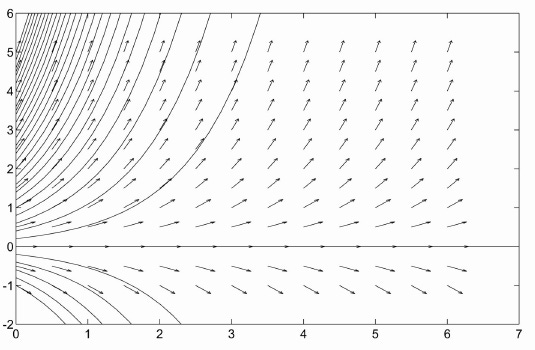

In math there is a field of study called “Chaos Theory”. It is defined as follows:

“Chaos theory is an interdisciplinary scientific theory and branch of mathematics focused on underlying patterns and deterministic laws, of dynamical systems, that are highly sensitive to initial conditions, that were once thought to have completely random states of disorder and irregularities.”

I like to imagine businesses as dynamical systems, which can be modeled as such:

The funny thing about reality however is that it is single threaded. Only one of these lines will be correct, so how do we determine which?

Let’s take CVNA as an example since I’ve written about it before. In my previous article I showed why I did not believe the company would go bankrupt from operations over the next few years. I shared that I believed ALLY had little to no incentive to break their MPSA agreement. I shared that EG2 and EG3 being frauds simply made no sense. I shared that SG&A per unit was overstated and obfuscated underlying leveraging due to growth investments and buying customer cars. In combination, for the lazy first level investor these combination of factors may fully discount the investment, for my own underwriting they had almost no impact as I have high conviction that incentive paths will not lead those realities to fruition.

On the upside, I believe that CVNA is clearly competitively differentiated. Customers clearly prefer delivery to no delivery. Customers clearly prefer quicker delivery than slow delivery. Customers clearly prefer high selection to low selection. Customers clearly prefer a frictionless experience. Customers clearly are willing to pay a premium in APR’s for these factors. Competitors (VRM, Shift, etc) clearly can barely remain solvent. For these reasons, I am highly convicted in my thread and the corresponding returns being correct, my job is to simply hang along for the ride and update accordingly.

The same logic applies to CDLX and META but we will save that for a different time.

The end point simply is, my goal is to have situations in which I can maximize the delta between my model and consensus model (duh). I believe these companies with highly uncertain situations and futures, “intrinsic value volatility”, will on average provide the best opportunity and I will continue to write about them as I find them. My interest in CVNA and CDLX was piqued exactly when they ran into issues, not prior. I like to think of it as event-driven fundamental investing, all the uncertainty, much less attention, and far less of the boring spreadsheets.

Whether my own capability to produce said “alpha” is correct or not, hopefully my writing can provide at least someone with some value and enhance my own thought process. I appreciate you my dear reader taking the time to review my rambling. To receive my following META and CDLX write ups feel free to subscribe.

Thanks for the write up! I hope you will continue to write about these companies. My feedback about these companies are position sizing which 80% of the game :)