Reflection On Managing Money

And other such interesting titles

Hello once again friends, today’s episode is about a journey I started in 2021 that ended this August. Said journey saw me go from a fresh college grad that had no idea what a 10-Q was to managing a portfolio. Giving a mostly self taught analyst access to a pool of capital with a ripe 2 years of experience is certainly atypical, but I like to think I did alright.

Anyways, the purpose of this article is not to sarcastically pat myself on the back, we’re here to learn and grow! Writing is always a great way to prompt some self reflection, so hopefully this is helpful for myself, and for those of you reading. We’ll get back to analytical content tomorrow if you’d like to subscribe. Cheers.

Setting The Scene:

My background is one quite atypical for the buy-side, which I’ve mentioned before but we’ll briefly do so again. I graduated with a degree in math in 2021, and let’s just say Covid making my last two years of college online didn’t do a whole lot to give direction. In March of that year I started applying to basically any job that had “analyst” in the title as they all paid decently well and I didn’t really care what I was going to do as long as it never involved writing a proof again.

For whatever reason, I was hired to work for a family office, essentially tasked with monitoring their internal equities portfolio as well as manager allocations to ~10 long only funds. When I say family office to be clear it was one guy who made a bunch of money and instead of retiring decided to read a bunch of Buffett and hire college students every few years so he could have 1-2 people sanity check him (and handle paperwork). His eternally gracious wife for some reason tolerated this for the most part.

The blessing and curse of such a situation is that you are essentially forced to Figure It Out in regards to effectively doing your job. There were no endless nights working in IB honing my model formatting skills. There were not years of “rigorous” training in PE on valuing companies and analyzing operations. Just a Google Drive full of hedge fund letters and a goal of beating SPY by 3% annually.

With the help of my wonderful ex-coworker I managed to not get fired for the first 2 years as I learned, which also just so happened to coincide with a significant market crash, and total economic mayhem. In all honesty such a situation is arguably a blessing. The obvious reason being my “Official” track record starts in 2023. The less obvious one being that one of the best ways to even the playing field and outperform despite a lack of experience, is to work in a field where nobody has any idea what is going on.

Like if we look back objectively, it’s pretty hilarious how well everything went. The economy was suddenly ground to a halt, tanking markets. World health organizations were lying, incompetent, or both. Unruly populaces were locked down, unlocked down, locked down again. Then we just printed infinity dollars of stimulus money and hoped for the best. Suddenly the infinity dollars of stimulus started to create inflation, oops, so interest rates ballooned fast enough it killed numerous banks and had (some) people wondering if Schwab was liquid.

Then to cap off all of that covid fun, OpenAI drops ChatGPT and we just kinda moved on to “Stocks Always Go Up” AI edition. A global pandemic, credit crunches, absurd inflation, and SPY is up >100% in 5 years. Not a whole lot of people could have predicted that.

All that to say, I’d argue it was a pretty interesting time to get into public equities. Absurd highs, absurd lows, more absurd highs, all in such a concentrated period! Earlier this millennia markets at least had the respect to wait 7-10 years per cycle. While I of course am no historian on the topic, I’d say the job and markets themselves have changed quite dramatically over the past 5 years compared to prior periods. I do genuinely think there is still tremendous room for alpha basically irrespective of strategy, just take a look at META’s stock chart or quantum or BYND or OPEN or something if you want to argue markets are super efficient.

Separately, I do feel like I’m wired pretty well for money management. To date I haven’t withdrawn a cent from my PA despite the fact I can now technically afford the supercars and watches I was obsessed with in high school. The numbers are just numbers for the most part. I still felt like throwing up occasionally as I watched my annual salary get erased in 5 minutes post earnings every so often, but overall the nerves were honestly less than I had playing junior golf tournaments as a child.

I’m also much more concerned with “being right” than being a people pleaser, which led to the occasional hiccups with my old boss as I’ll happily argue until myself or the other party is convinced. Not “being right” in the sense of refusing to be wrong, but truly in the “if you know better please explain to me way” which is not exactly your role in your early and mid twenties, but alas. I do think it’s quite important to “manage” ones spine to not get overridden by thinks that make no sense, which can be quite frequent in markets.

And given all that, I’m not actively looking for a new role as an analyst/managing capital (for now?). So why?

Gardening Leave:

I’ve been asked a couple times about raising money for a fund. I am by no means an expert in the matter, but I do have a few thoughts.

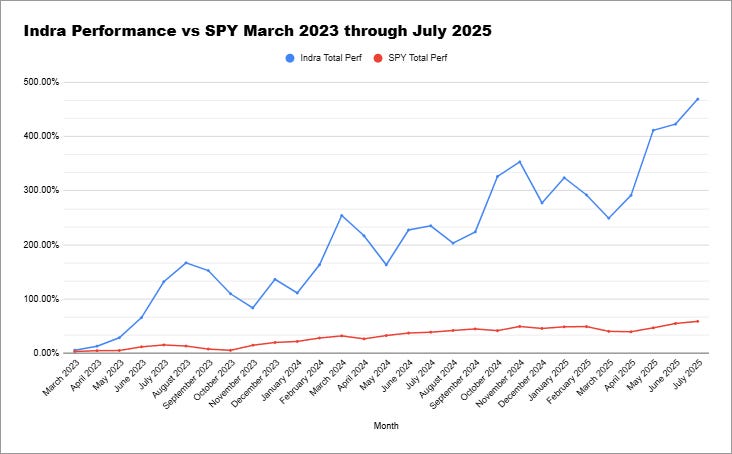

Firstly I’d say that while the track record I have is absolutely phenomenal, it does have some tarnishes, both to potential investors and to me. The main issue is concentration. Running long only at 100% Net Exposure with 4-5 stocks is not something that typically gets allocated to. Like realistically as a percentage of the AUM in the industry, I’d imagine it’s miniscule. An allocator can always tell themselves it was a few lucky bets, not a proven system of generating excess returns. The whole obsession with proven systems means the largest pools of capital are actually managed by firms that underperform SPY.

Of course I am partly joking, the quants and multi-managers of the world do seem to be quite good at extracting value given the circumstances, just a bit too black box for my taste if I were to be dumping in billions.

The investments I made in the account I managed basically all worked out (besides CDLX, which gave tastes of glory to make the fall that much sweeter). At the same time, many many things worked out. It’s a fun exercise to go through your watchlist/old starter positions and see that despite all the narratives if you had just thrown a dart in 2023 it likely returned 100-200% or more since.

Carvana of course was the primary exception to this, which thus far has returned about 36x on the initial investment in that account, bless the Garcia’s and hopefully not jinxing anything. Carvana took up the majority of my time and I really lived and breathed Carvana for months in late 2022/early 2023. I honestly do not understand how managers can have 15, 20, 30+ stock portfolios that they feel they truly have an edge on. On the flip side, allocators and other market participants have no idea how I sleep at night with 4-5 positions, and currently ~3 in my PA.

I’ll get more into theory later, but the point is that my sense is allocators really wouldn’t be chomping at the bit to allocate to anything I’d fundraise for. I also feel some responsibility to prove to myself that continued outsized returns are repeatable before I took responsibility for large pools of capital. Experimenting with retirement funds seems dubious despite the significant upside of personal compensation.

Now assume I could theoretically find allocators to write me a check, what would that look like? I’m personally just not really the type of person to enjoy the monkey dance of raising capital. I’ve been on the allocator side as well and it’s truly absurdly hard to get confidence someone will do well if you don’t know them personally.

The natural conundrum any smart allocator will face is that there is no solved method of obtaining alpha.

Now this is rather trivially true, otherwise it wouldn’t be alpha, but really sit and think about it for a moment. The way the majority of dollars are allocated to managers is via check lists and investment committees and a whole lot of systems. So not only do allocators have to fly blindly and hope their systems are arbitrarily good at obtaining alpha, but it has to generate enough alpha to justify fees, time spent, and taxes (if applicable).

So yeah just get some confidence a random guy your employee met via a cap intro program will outperform SPY by 5%+ indefinitely.

I do all of that calculation in my head and just think “wow I would probably be really annoyed having conversations where we skirt around how absolutely absurdly hard that is”.

So instead I opted for gardening leave, aka tinkering around with SaaS and AI. It’s entirely possible I more formally explore equity management again in the future. As I said a large portion of my decision is basically me saying “hey can I really trust myself to do this well consistently” and time/iteration certainly solves that. And to insert some more sarcastic bragging that hopefully doesn’t jinx anything, at this rate my PA is growing 100% a year, so maybe I won’t need to be a monkey for seed capital soon!

More On Theory:

If you didn’t get roll your eyes hearing a 26 year old discuss an industry he participated in for a few years like an old man, now you can roll your eyes at said 26 year old discussing investing theory! Is it good theory? Or are past returns not indicative of future results? Fair warning, I do ramble here so feel free to skip.

An important thing to keep in mind when reading this article and others, is that everyone who’s done well with stocks thinks they are good at picking stocks. Even many who don’t do well just think they are unlucky. Part of the problem here is that there’s not really a good fundamental basis for what makes a good stock picker. Like someone who is “good” at golf we can just take a look at their handicap. Someone who is “good” at Chess we can take a look at their elo. Stock picking is much different, as the end result can be totally detached from the quality of work and ability.

CDLX for example has at times been a multi-bagger return, and at times been a 75% loss. At times it was legitimately just a very good bet based on informational advantage. Generally, it’s been awful to hold longer term. If the company turned itself around tomorrow and 100x’d in 5 years would everyone who sold this year be an idiot? Would those who bought it for $3 during a Twitter induced pump be genius stock pickers?

Over longer periods of course returns will normalize, but that’s a pretty awful way to determine current and future alpha, as perhaps the driver of alpha is temporary. Being early to AI was legitimately life changing for many NVDA investors for example, that doesn’t necessarily mean they are exceptional general stock pickers over longer periods, but their track record will basically always trounce the S&P due to that very good bet.

So back to theory - how can we consistently find differentiated positive results to hit the NVDA’s of the world repeatedly while also being cognizant that any systemic way to do so is implicitly impossible?

Before diving in I have two main beliefs that support everything else:

The world is essentially deterministic

Your model of it is wrong and you don’t know how

The “unknown unknowns” makes some people shake their head and just toss money in an index, which is quite honestly the best way to go for most, but that’s not why we’re here! We all want to outperform each other! To do so we just need to make a wrong model that’s right.

My basic hypothesis is that the best way to do so is play Show and Tell with everyone else.

Like yes, it is quite important to have emotional temperament, be able to open excel, be able to read, and what have you. Those skills however I would consider “table stakes” if our goal is to significantly outperform the market.

What’s interesting is that they weren’t always right? Like if we go back in time to 1930 or something. I’d imagine the average investor had no fucking idea what was going on, as did the average company. Like it’d be absurd to think the world has gotten drastically better at sports, literacy rates, academic discoveries, whatever, and not investing. In the 1930’s you probably couldn’t find a high school teaching calculus, yet nowadays we have kids reciting real analysis textbooks in elementary school. The men’s 100m sprint winner of the 1932 Olympics would not even be the best high school sprinter in the US these days.

The human race and thus markets are dynamic and continuously grinding towards higher performance, so I’d argue what’s more important than basically anything else is to continuously work to understand what everyone else is doing, because what you are doing being good or not depends heavily on them.

In simple terms, the number one thing to care about is what a stock’s price is, what expectations are, and why those expectations are believed.

This is actually a really hard question surprisingly! It’s also I imagine part of why AUM is moving increasingly towards the quant/pod model which is much more in tune with this idea.

I think it naturally kind of follows that in the earlier days of professional asset management all it took to be quite good was some fundamental analysis. I’d imagine 20-30 years ago audits were worse, the average investor was less informed, alternative data sources were far less common, computers weren’t arbitrarily sniping massive price inefficiencies, etc. Nowadays investors are more informed, computer pick up free money much more often, it’s easier to get reads into business performance and cover numerous companies.

In a non-systematic world, a system becomes alpha, then the system becomes standard, and front-running the system with data becomes alpha, and so on.

So for us lowly stock pickers, what do we do? Conceptually the game being played now I think is very rewarding for 9-18 month narratives. I believe this as I look at AUM flows moving towards quarterly/data release firms and repeatedly see very high volatility for “narrative violations”, both up and down.

Some examples recently are:

META dropping to $80 on CapEx/Metaverse/Apple changes

The CapEx was clearly not just Metaverse

Where else were companies going to buy ads? Newspapers?

GOOGL dropping to $140 on “AI loser fears”

They were trivially performing very well with enterprise model capabilities

TPU’s are clearly very good

ChatGPT was obviously being used for queries that didn’t have high overlap with Search monetization

In these cases you performed exceptionally well with a very very basic thesis, because the narrative was a near quarters data narrative that seemed totally out of sync with the underlying technology.

Since price depends on what other people believe, I think it also follows that stocks/industries that don’t fit the “norm” will have higher outcome variance, positive or negative. Financial markets clearly underestimated AI, and arguably continue to do so. Having a basic understanding of that area has been a massive alpha pool. Similar to SaaS being poorly modeled earlier this decade, or the internet being massively overvalued in the 90s. As the world continously trends towards “data enabled” understanding, being able to contextualize can be alpha.

How does one contextualize? Depends on industry and is very hard. This is another part of why I’m taking a swing at a non-investing focused role. My conviction in Google was gained because I had time to play with their products and not track 30 arbitrary stocks each day. If Google was more private with their models and not giving them away basically for free it’d be harder to tinker with. CDLX for example might land a massive new partner tomorrow and we’d just not know until it’s explicitly stated in an 8-K. This is interesting because intuitively mega caps would be more well covered and harder to unlock alpha in than small caps right? So it’s very difficult to truly know ahead of time in a systematic way how to really properly understand a given company.

Carvana was a fun one because bears were and still are very vocal about their thesis, which was clearly outright incorrect. Of course random bears on Twitter aren’t the majority of short volume, but it’s helpful to understand opposing arguments and I sort of obsessively sought them out. Battle ground stocks are honestly easier for me to own because of the clear bear thesis. It’s much easier to work backwards showing something false isn’t true, than asserting a company has the mandate of heaven to grow bottoms up. I always just thought “if Carvana can have slightly down units on insane price taking, longer delivery times, macro struggles, and incessant negative headlines, I don’t know what they will grow as that normalizes, but it’s much higher”

Going purely on relative momentum of course can be bad and is part of why CDLX did so poorly for me. The idea was “the product is growing X% and getting better with no real alternatives so it should grow more”. What this failed to consider was what their customers were thinking, where they were basically happy to grow budget in the new fun channel that was ramping from volume growth, and despite the product getting better over time it wasn’t a “hot thing” anymore to be doing card linked offers, so budgets were moved (plus mismanagement, etc).

In really simple terms if I look through the investments that have done well for me like GOOGL META CVNA BLND NTES TPR etc the core theme really something like “very good product has temporary narrative violation that will be quickly resolved or maybe they even accelerate”. The issue with CDLX is the narrative violations were never solved, they just compounded, and honestly the product wasn’t really that great from the eyes of advertisers irrespective of things like “ROAS” (partly why I have a preference for B2C investing).

I’d imagine this style loses some of its edge as AI gets better at picking up sentiment and such from a wider lens. It will likely also be relatively harder for companies to bounce back from narrative violations in tighter financial conditions.

Overall though, this section is getting very long and a bit of a ramble, just wanted to note some thoughts down on the ever elusive topic of investing theory before going back to just posting some raw analysis. We’ll see what works throughout the rest of 2025 and into 2026 and I’ll keep everyone updated, fear not.

Next:

Enough long introspective stuff. Tomorrow we get >100% of my net worth reporting earnings as CVNA/GOOGL represent ~95% of my account which is ~120% net long.

I’ll post an update on those tomorrow with the help of some Clarity AI features that are hopefully publicly scalable soon. More on that later as well. Cheers.